Born: Valparaíso, Chile – December 7, 1917

Died: Albuquerque, New Mexico – February 10, 2003

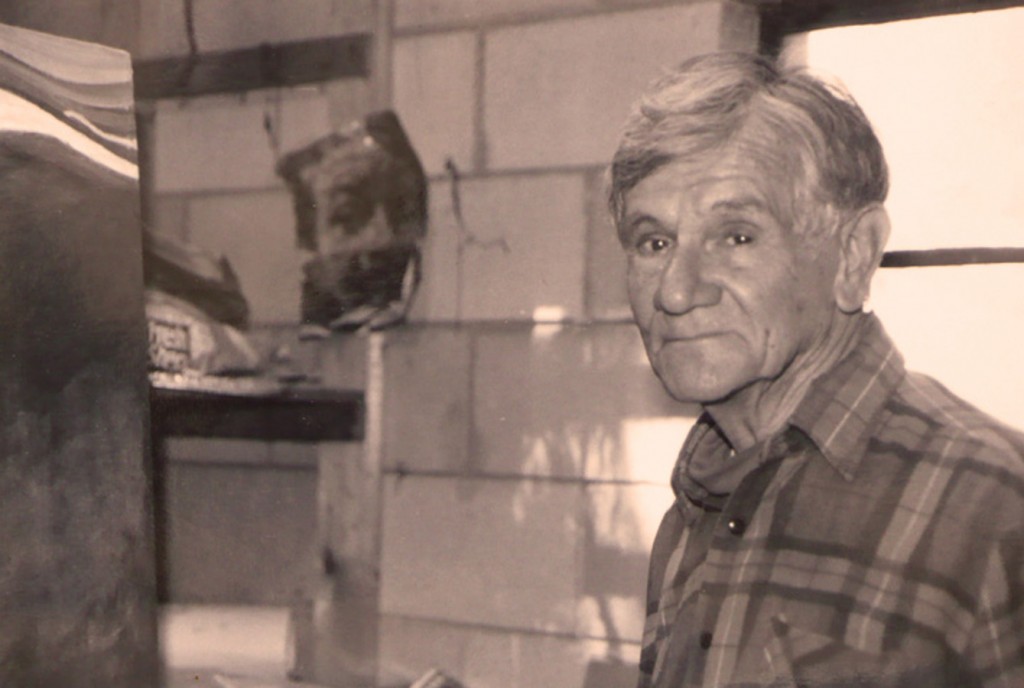

American Artist, 20th Century: Painter, Abstract Expressionist, Modernist, Art Professor

Childhood

Enrique Montenegro was the son of renowned Chilean writer and journalist, Ernesto Montenegro, author of Cuentos de mi tío Ventura, and of a progressive mother from San Francisco. Enrique was the second of four brothers. The itinerant nature of his father’s profession, which involved writing for newspapers on both continents, resulted in the the family’s traveling between Chile and the United States, causing the children to adapt to two cultures and languages. So it was that Montenegro’s first experiences were divided between the provincial environment of the small village of Almendral, Chile at the foot of the Andes and the throbbing activity of cosmopolitan New York City. His mother was independent-minded, with mystical tendencies, and had varied interests that included acting in silent films and studying philosophy with Bertrand Russell at Columbia University.

Montenegro’s first memorable encounter with painting was, in fact, through his mother who, while living in New York City, took her four sons to the Nicholas Roerich Museum on the Upper West Side, to view the work of the painter-philosopher, whose mysterious landscapes of the Himalayas were no doubt to make a lasting impression on the future painter. Curiously, hints of this Russian painter’s colors and even themes evoking the beyond are evident in Montenegro’s late paintings.

Young years and adulthood

In his youth, again having returned to South America from the United States during the depression, Enrique and his brothers were to accompany their father to Buenos Aires where he worked for the newspaper La Nación. There the sons were also to find jobs, Enrique working for a British bank and spending his free time drawing and painting.

It was in the outskirts of Buenos Aires that the artist was to find a teacher of painting, a certain Pedro Olmos, who helped him to develop the secrets of his craft and begin to paint in earnest.

During this period, he was to have an experience that changed the trajectory of his life. While he and his younger brother made a trip to Tucumán in northern Argentina to draw and hike, the two young men were taken for insurgent rebels and apprehended by the police. Being completely unaware of the local political turmoil of the area, the two were detained in the town jail for three entire days until their father was able to rescue them by convincing the police of their innocence. The dampness of the cell and the fatigue were to take their toll on Enrique’s health causing him later to contract pneumothorax. Upon returning to New York years later, at the height of the war, he would find himself thoroughly debilitated, laid up in bed for half a year in Bellevue Hospital with collapsed lungs.

Formal study

Montenegro gained his Bachelor of Fine Arts at the University of Florida, Gainesville in 1944, where he mastered the techniques of mural painting and printmaking in the socially evocative style of such Mexican muralists of the time as Orozco, Rivera, and Siqueiros.

In 1945, he was to earn a scholarship for post-graduate studies at the Art Students League in New York, where he worked to perfect his skills under such artists as Reginald Marsh, Morris Kantor, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Bordman Robinson, among others.

Now a painter in his own right equipped with the requisite credentials, Montenegro was appointed painting and drawing instructor, the youngest to teach in the art department, at the University of New Mexico. There he was colleague-instructor to Richard Diebenkorn and Agnes Martin, and became part of the group of southwestern painters and other visiting artists such as Raymond Jonson, Adja Yunkers, Douglas Deniston, Alice and Jack Garver, Ed Corbett, Van Deren Coke, Clinton Adams, and Robert Walters.

It was in Albuquerque that he met his future wife and mother of five children, a dedicated musician and pianist who, after graduating from Carleton College in Minnesota, studied with the Swiss pianist-conductor-composer, Rudolph Ganz.

Now with a small family, Montenegro moved to the old silver-mining town of Central City, Colorado so that he could work in Denver teaching evening art classes at the Opportunity School and the Art Museum, and continue developing his vision and painting style. It was at this time that he was singled out as an emerging American Abstract Expressionist painter and featured, together with Richard Diebenkorn, in a spread for an article in LIFE Magazine, November 1957, entitled “Look of the West Inspires New Group of Painters.” During this period, he also received both the Denver Art Museum Purchase Award and the prestigious Catherwood Foundation Award for European Study. Taking advantage of this award, he traveled to Europe and saturated his vision with the works of the great masters.

From Denver, Montenegro was invited to teach at the University of North Carolina. His teaching tenure coincided with the presence of the world-renowned Rembrandt authority and former curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dr. William R. Valentiner, then director of the North Carolina Museum of Art. Valentiner took a special interest in the young painter’s work, resulting in the selection of three of his paintings for the museum’s permanent collection.

Like other painters such as Diego Rivera in his famous Detroit mural, Montenegro was to paint the portrait of the Rembrandt scholar, which now hangs in the museum.

His next teaching post was at the University of Texas Art/Architectural Department where he was to meet his lifelong friend and fellow reflective painter, Hiram Williams. Their lives were mysteriously to mirror each other, from birth to death, almost to the day. Williams was to cite Montenegro as a forceful, influential painter in his artistically provocative and didactic Notes for a Young Painter.

During this time, Montenegro exhibited his work in the Felix Landau Gallery in Los Angeles and Parma Gallery in New York among others, and was chosen to exhibit in various expositions such as the Krannert Museum Exposition for Drawing and Painting. His work was promoted by the art collector and museum director, James B. Byrnes, the first curator of the Los Angeles County Art Museum (1946), Director of the North Carolina Museum of Art, and New Orleans Museum of Art, resulting in his paintings finding their way into private collections such as that of the actor Vincent Price, among others.

From Texas, he was invited to teach at various other colleges and universities including Mount Holyoke College, Pennsylvania State University, Brown University, Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, Towson State University, and Bowling Green State University.

As both a painter and teacher Montenegro’s influence was wide-ranging, and left a mark on a legion of painters, draftsmen, curators, and art historians alike that were to form the next generation of artists.

The painter

As a painter his style was unique and varied. Initially, he belonged to the dynamic movement of the Abstract Expressionists, but was to go on to develop his own visual language that translated into landscapes, tablescapes, and figures with forceful, “muscular” tension articulated by masterful brushstrokes and sensitive color schemes. Later he was to blend this unique language with classical technique to express social commentary on the tumultuous American scene comprising the years between the Sixties and the end of the Twentieth Century.

Montenegro was to prophesy the beginning of a violently nervous era in America particularly with his Goyaesque “Kennedy Assassination” series, conceived and executed only weeks after the actual event in 1963. These dramatic paintings were followed by forceful themes depicting the urban scene —oddly idyllic wastelands of parking lots, shoppers frozen in action beside the metallic armor of a car door, pedestrians in mid-street guided off canvas by arrows, interiors with figures wrestling with a complexity of silent tensions, mannequins in shop windows, rough pavements punctuated by a single human hand or foot, and luscious landscapes capturing the varieties of Nature’s many moods— all unfolding before the viewer in delicate colors manipulated by a sophisticated use of composition and dynamic planes.

In his last years, Montenegro returned to the Southwest, where his work apparently moved full-circle in his representation of the ancient landscape of sleeping volcanoes, windswept mesas with brooding clouds, poplar trees in the rain ––this time in a style that was the culmination of a life of observation and experience informing his brushes with philosophical depth.

Montenegro lived his life as a painter par excellence. Painting was the center of his existence and his activities as a teacher were just the generous overflow of this intense dedication. Against the current of the times in which he found himself, he stubbornly kept to his own vision and refused to be caught up in the fickle, shifting trends of the art market. Above all, he was true to his own Muse and uncompromising in this regard to the end.

* * * * *